Evaluating the Security Model of Agentic Browsers

AI Browsers create a new semantic layer above tabs that is a new paradigm shift for browser security. This creates new attack vectors that affect users as adoption scales widely.

1. Introduction: From Browsers to Agents

Agentic browsers, such as Perplexity’s Comet and OpenAI’s Atlas, mark a transition from user-led browsing to autonomous web interaction that fulfills user requests. These new browsers integrate persistent memory, natural-language interfaces, and automated task execution spanning multiple tabs and domains. They cast a new frontier of the web for businesses and users but pose new risks that are yet to be fully understood.

Previous threat boundaries were governed by rigorous security policies: Same-Origin Policy (SOP) and Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS). However, agentic browsers redefine the threat surface, rendering these policies virtually useless.

When an AI assistant follows malicious instructions from untrusted webpage content, traditional protections such as same-origin policy (SOP) or cross-origin resource sharing (CORS) are all effectively useless. (Brave)

1.1 Security Threats

Let’s quickly cover three security threats.

CometJacking

Research by LayerX recently exposed an exfiltration attack in Perplexity’s Comet browser via a weaponized URL. A simple query was able to get user credentials and encode them in Base64 before sending to the attackers domain.

Instruction Injection

In this example, the attacker does not even need to direct a user to their compromised website via a phishing link. Instead, the attacker can leave a malicious prompt on a public forum (e.g. Reddit) where the AI browser will read and execute the instructions. These instructions could command the AI to extract user credentials, recover an OTP from Gmail and take-over the Perplexity user account. (Brave)

Image Steganography

In this example, the attacker can embed malicious instructions camouflaged within an image. These instructions would also be read by the AI agent’s OCR capability and can lead to data loss or account take-over.

Even though Comet and Dia browsers are built on the LayerX security platform, they are still at risk of cyber-attack. Hopefully this sheds some light on the potential vulnerabilities for users of AI browsers.

To understand how this happens first let’s compare the architecture and security controls behind established browsers versus agentic browsers. We will look at both Comet and Atlas as examples covering their architecture. Then we dive into how agentic browser attacks occur by studying the LayerX discovered vulnerability. Finally, lets look into additional attack vectors for AI systems, before looking into user and business recommendations to safeguard data.

2. Core Browser Security Architecture

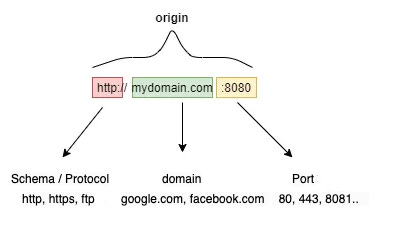

2.1 The Same-Origin Policy (SOP)

The SOP is the cornerstone of web security. It restricts how a document or script loaded from one origin can interact with resources from another. An origin is defined by three parameters: scheme, host, and port.

For instance, a script loaded from this address can only read or modify resources from the same origin.

https://example.com:443/page

→ scheme: https

→ host: example.com

→ port: 443.If that script tries to access http://example.com (different scheme) or https://sub.example.com (different host), the browser blocks it.

This mechanism is essential for confidentiality (preventing unauthorized data reads) and integrity (blocking unauthorized modifications). Without SOP, pages could freely query your authenticated banking or email sessions from unrelated tabs—a direct path to credential theft and session hijacking.

2.2 Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS)

SOP, while secure, is rigid. Web developers often need legitimate cross-site communication, such as a shopping site pulling prices from an API or a dashboard querying an authentication provider. CORS was introduced to selectively relax SOP restrictions. (AWS)

CORS adds HTTP headers the server uses to declare which origins are allowed to request its resources. There are two main types:

Access-Control-Allow-Origin:grants explicit permission for a site to allow access from a requesting site. For example, if https://news.example.com requests to access to data from an API at https://partner-api.com, then developers at partner-api.com would add explicit permissions to allow requests from news.example.com.HTTP

OPTIONS:for complex requests, the client sends a preflight requests with a HTTP method, content type and origin to the server to verify privileges. A successful preflight response (i.e. status 200) leads to the client kicking-off the actual HTTP request for sensitive data or modifying a resource (e.g. modify, delete).

These explicit permissions on the server-side enforce a server-controlled trust boundary, to prevent arbitrary data sharing. Both SOP and CORS are client-enforced at the browser layer, forming the first line of defense against unauthorized cross-site data flows.

2.3 Sandboxing and Data Storage

Beyond request restrictions, modern browsers isolate processes to contain execution. Every tab operates in a sandbox preventing a compromised process from affecting others. Sensitive credentials (cookies, passwords, credit cards) are stored in encrypted local stores accessible only to authenticated users.

Features such as Content Security Policy (CSP), secure cookies (HttpOnly, SameSite), and permission prompts protect against data exfiltration and drive-by code injection. These mechanisms are predicated on a user-driven interaction model where actual user intent (i.e. deciding what to do with information, changing between tabs, evaluating risk of actions) and not autonomous AI logic, initiates sensitive operations. This is where the problem begins, when we hand-off the user evaluation to AI.

3. Agentic Browsers: Deep Architectural Analysis

3.1 Overview

Agentic browsers represent a new class of software that merge web rendering engines with LLM-driven memory architectures. Instead of being passive tools for user input and content display, they integrate persistent AI assistants within the browsing core, i.e. agents that perceive, reason, and act across different tabs and contexts. This is achieved through a hybrid control model that overlays traditional browser processes with an AI coordination layer.

The two prime exemplars of this model — Perplexity’s Comet and OpenAI’s ChatGPT Atlas — deploy different technical mechanisms but share the same philosophical aim: to make browsing a semantic operation rather than a mechanical one.

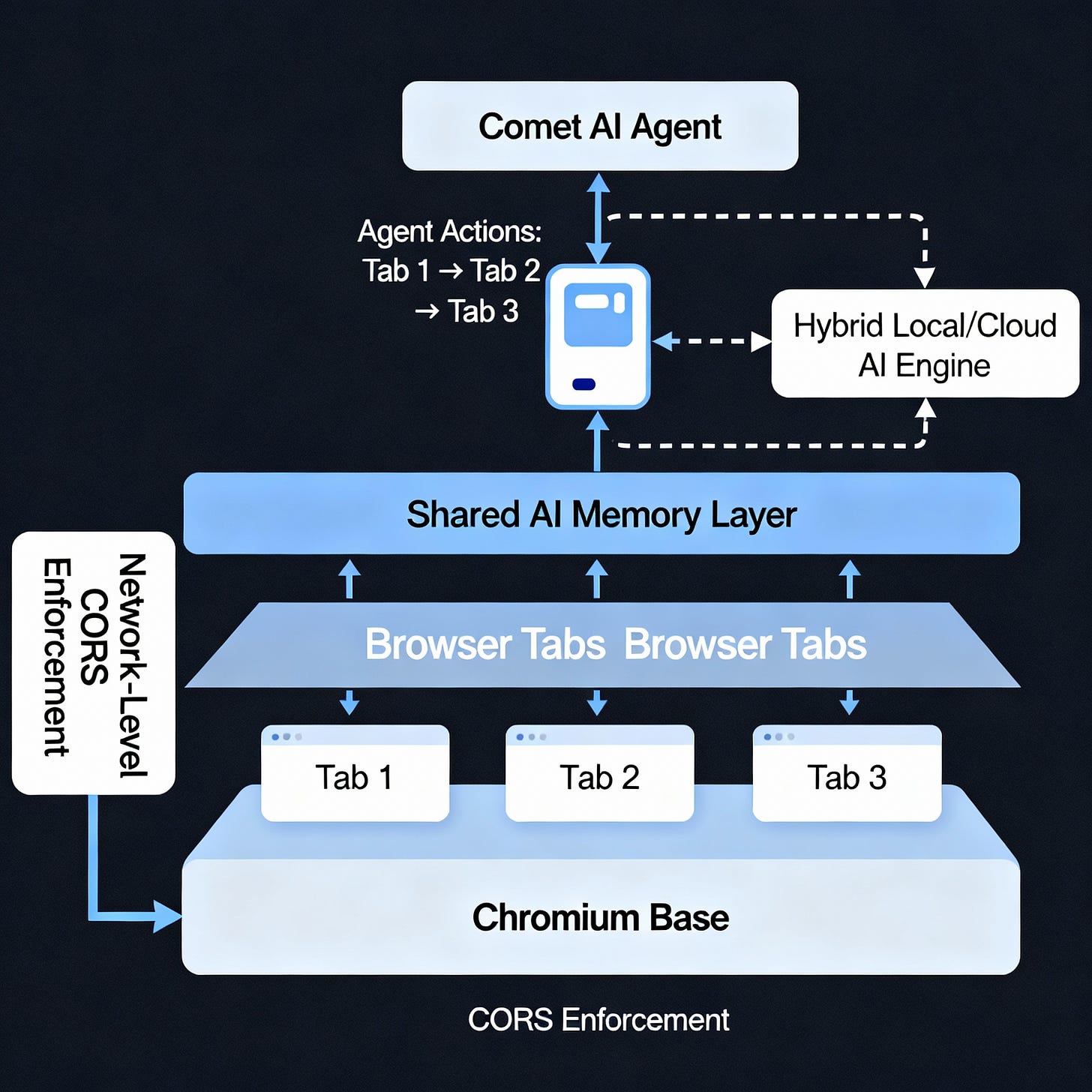

3.2 Perplexity Comet Architecture

Comet is built on a modified Chromium base, architected around three interlinked planes: the User Interface and Agent Layer, the Extension Bridge, and the Execution Kernel.

User Interface and Agent Layer (UI/AI Plane)

The visible browser canvas is powered by Perplexity’s LLM-driven co-pilot interface.

This layer runs a web-based agent at

perplexity.ai/sidecar, which acts as the command-and-control interface. Users issue natural-language prompts here.The agent understands the browsing context, generates structured “browser actions” (e.g., open tab, read content, summarize document), and orchestrates workflow tasks across tabs.

Extension Bridge

Key to Comet’s design, revealed via reverse engineering and developer testing, is a hidden Chromium extension that handles all privileged actions.dev

This extension receives serialized JSON commands from the web-based agent (such as

OPEN_TAB,NAV_SEARCH, orSEARCH_HISTORY), interacts with the native Chromium APIs, and returns structured responses.The extension notifies the UI layer with results, effectively creating a two-way communication pipeline between the cloud-based AI and the local browser instance.

Execution Kernel and Memory Subsystem

The execution kernel operates like a sandboxed OS within the browser. However, Comet introduces a Shared AI Memory that links across all tabs, allowing real-time contextual awareness.

This memory includes semantic embeddings of text the user has interacted with, enabling “cross-page cognition.”

The memory is part cloud-stored and part local, with synchronization events controlled via API endpoints hosted by Perplexity’s servers.

In brief, Comet fuses Chromium’s site isolation model with an LLM-driven coordination controller. While CORS and sandboxing remain operational at the network layer, the AI layer can access content via the Document Object Model (DOM), bypassing origin-based reasoning boundaries.

3.3 OpenAI Atlas Architecture

Atlas, unveiled on October 21, 2025, rethinks the interface paradigm entirely by embedding ChatGPT as the browser’s logic controller. (Intuitionl Labs)

Integrated ChatGPT Core

Atlas uses the ChatGPT reasoning engine directly within the browsing frame — not as a separate sidebar extension but as a threaded process tied to the DOM renderer.

The core ChatGPT process interprets page content in real time, classifying it semantically (e.g., “this page is a form,” “this is a product list”).

Every content segment passes through contextual embedding pipelines, generating a short-term vector store unique to each session.

Agent Mode Subsystem

The “Agent Mode” layer allows ChatGPT to independently perform multi-step actions: form submissions, shopping tasks, or navigation flows.

A coordination manager sits between the renderer and the Agent Mode layer, creating action queues.

To preserve safety, OpenAI employs sandbox-bound execution rules: while the agent may fill forms and click buttons, it cannot install extensions, execute local code, or access system files.

Persistent Browser Memory

Atlas introduces 30-day Browser Memory Pools, encrypted and server-synchronized.

Memory entries record page summaries, user instructions, and session context.

Unlike Comet’s dual local/cloud split, Atlas’s memory is stored almost entirely on OpenAI’s infrastructure, allowing context traversal across devices.

Security Composition

The Chromium base still enforces SOP, CORS, and TLS certificate checks.

However, Atlas’s AI-based memory model means that data boundaries become semantic. For example, if a user views medical information and later shops for insurance, the model can logically infer correlations between sessions — an architectural gray zone between contextual convenience and cross-domain data exposure.

4. Redefining the Browser Security Model

4.1 From Isolation to Cognition

Traditional browsers center their security around process isolation: each origin runs in a distinct sandbox with no access to another’s code, cookies, or DOM elements. Agentic browsers like Comet and Atlas invert this principle — they introduce a central semantic orchestrator operating above these silos.

While SOP and CORS still govern direct script and network operations, they no longer confine how the AI model reasons about content. This means:

An AI agent can indirectly merge understanding from different origins, forming composite insights beyond CORS’s visibility.

Data does not “leak” at the network layer. Instead it “flows” at the reasoning layer, through the agent’s summarization and synthesis processes.

This creates a new threat plane: not via code execution, but by semantic inference across traditional isolation zones.

4.2 The CometJacking Exploit: A Case Study

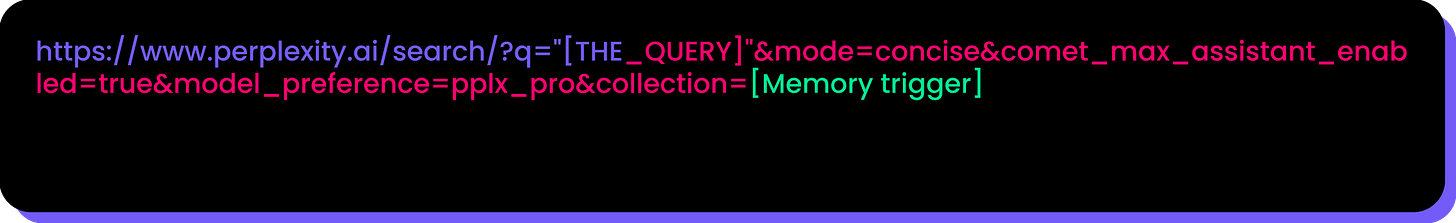

LayerX Security’s 2025 paper “CometJacking: How One Click Can Turn Perplexity’s Comet AI Browser Against You” (LayerX Security) and the corresponding TheHackerNews report outline the first real proof-of-concept exploit targeting this architecture.

The attack chain works as follows:

Trigger Vector: A user clicks on a crafted URL embedded in an email, blog, or search result. The URL includes hidden parameters designed to be parsed by Comet’s memory-aware AI controller.

Agent Hijack: The parameters contain instructions (injected prompts) that resemble legitimate analytical queries such as “summarize my last email” or “show my Calendar.” Since the Comet agent trusts its own historical memory, it processes these requests from its context, not from the webpage’s script sandbox.

Memory Exfiltration: The AI, acting helpfully, retrieves sensitive contextual information (emails, notes, or calendar entries) from its shared memory system and compiles them into a concise “summary,” which the attack page silently encodes and exfiltrates through a network anchor tag.

Bypassing Classical Protections:

No CSP, SOP, or CORS violation occurs — the commands operate entirely through trusted browser processes.

The LLM acts as a human proxy, following adversarial instructions embedded in natural-language data rather than malicious script calls.

According to LayerX, the exploit achieved full agentic compromise with a single URL click, while all HTTP-level security policies remained intact.

This attack exemplifies the difference between transport-level security (which stayed uncompromised) and semantic-level trust (which was exploited). It theoretically mirrors what OWASP now defines under LLM03: Indirect Prompt Injection.

4.3 Architectural Consequences

These security exceptions underscore the paradigm shift:

Attack Vectors: Exploits now originate from data interpretation, not code execution.

Exfiltration Medium: Context synthesis performed autonomously by the AI.

Mitigation Gap: Traditional security frameworks (SOP, CORS, CSP) guard network boundaries, but not the reasoning boundaries of embedded agents.

For Atlas, OpenAI has implemented contextual action pausing — a safeguard requiring user reconfirmation when tasks span sensitive domains (e.g., banking or email). This demonstrates early defensive adaptation but doesn’t address deeper inference risks, such as cross-memorial reasoning leaks.

4.4 Broader Implications

This new model fundamentally redefines browser trust boundaries as users delegate more tasks to AI agents.

Browsers are no longer passive executors, but autonomous agents interpreting and acting upon user intent.

The core question is shifting from “Which script can run?” to “What may the agent infer or recall?”

Developers and security architects must now treat AI inference logic as a mutable attack surface.

Future browser security models must extend below HTTP and DOM enforcement to include context validation, memory provenance, and decision auditability. This is the new “CORS” for cognition rather than connectivity.

These architectural developments in Comet and Atlas mark the frontier of post-SOP web security. Browser safety in this new paradigm hinges as much on LLM containment as on network isolation. CometJacking has proven that the weakest layer in the stack is no longer the code sandbox, but the human pattern the AI trusts the most: its own memory.

5. Threat Landscape: OWASP and MITRE Perspectives

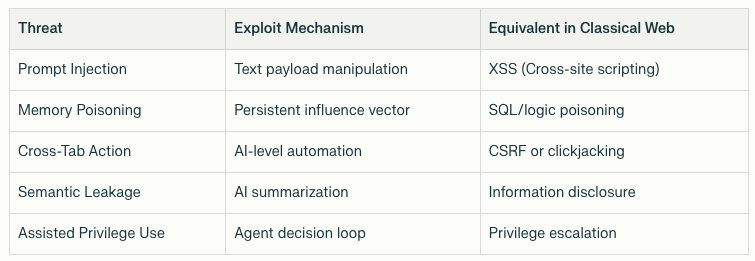

Agentic architectures intersect traditional and emerging attack vectors. Common classifications include of AI security risks include:

Prompt Injection (LLM01) – Text-based adversarial commands within web content can manipulate the agent’s behavior, leading to unauthorized data exfiltration.

Memory Poisoning (LLM02) – Persistent memory allows attackers to seed false facts or instructions, influencing later actions.

Privilege Escalation – Agents acting on the user’s behalf can perform actions relying on authenticated cookies or session tokens, replicating Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) patterns at AI scale.

CometJacking / Atlas Shadowing – Indirect prompt sequences triggered via malformed URLs or invisible input fields execute unintended actions across tabs.

Behavioral Profiling – Persistent cloud-side memory may capture private workflow data—browsing habits, credentials, or content summaries—forming new privacy attack surfaces. (CloudFactory)

6. Implications: When AI Breaks the User-Driven Model

The browser security model assumed intentional, observable user actions. Agentic browsers dissolve that assumption: decisions are inferred, context-driven, and sometimes autonomous. This introduces uncertainty in trust boundaries:

Who “authorized” an action when the AI acts autonomously?

Can memory integrity be guaranteed if influenced by dynamic content?

Do AI summaries infringe on data isolation between domains?

Even with perfect CORS compliance, unauthorized reasoning across origins breaches the spirit of the same-origin policy. It transforms browsers from sandboxed executors into interpreting mediators, which is a fundamental shift in threat modeling.

7. Mitigations and Recommendations

For Users:

Reduced privilege profile: Creating a separate profile with minimum access to financial and personal information to reduce the impact of a hack. Do not give the browser access to all your passwords, credit card, banking, government and social media information.

Isolated browsing profiles: use dedicated sessions for agentic tasks, e.g. content writing, separate from grocery shopping or online subscription accounts.

Disable persistent memory in AI browsers unless necessary.

Review AI logs for unexpected summarization or inter-site referencing.

Treat agentic browsers as automation environments, not secure personal sandboxes.

For Enterprises:

Adopt zero-trust AI governance, enforcing domain whitelists for agent activity.

Deploy telemetry for agent action tracing—capturing reasoning steps, not just HTTP events.

Encrypt AI memory and purge it on logout.

Extend Data Loss Prevention (DLP) systems to monitor semantic leaks.

Mandate approval flows for high-trust actions (e.g., purchasing, credential autofill).

8. Toward a Standardized AI-Browser Security Model

The OWASP AI Security Guide and MITRE ATT&CK mappings must evolve to define agentic-layer risks. Future frameworks should address: (OWASP)

Persistent memory governance and auditability.

Unified logging of AI-driven decisions.

Secure prompt boundary enforcement.

Cross-context sandboxing for semantic data.

Industry-wide cooperation combining browser vendors, AI developers, and cybersecurity standards bodies will be essential to design the next generation of defense-in-depth for cognitive systems.

9. Conclusion: Risk and Responsibility

Agentic browsers like Comet and Atlas represent the next paradigm of web interaction, one where the user becomes a collaborator rather than a controller. The underlying web security fundamentals (SOP, CORS, sandboxing) still stand, yet they are no longer sufficient by themselves.

The key challenge lies not in code execution but in intent interpretation: as browsers start reasoning, trust must shift from scripts and sites to semantic agents. Unless memory governance, human oversight, and transparency evolve accordingly, these tools risk turning human convenience into automated vulnerability at scale.

References

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/Security/Same-origin_policy

https://aws.amazon.com/what-is/cross-origin-resource-sharing/

https://www.gigenet.com/blog/openai-atlas-browser-ai-powered-chromium-review/

https://intuitionlabs.ai/articles/chatgpt-atlas-openai-browser

https://www.wired.com/story/openai-atlas-browser-chrome-agents-web-browsing/

https://www.lasso.security/blog/identitymesh-exploiting-agentic-ai

https://www.cloudfactory.com/blog/why-enterprises-cant-ignore-openai-atlas-browsers-fundamental-flaw

https://owasp.org/www-project-ai-security-and-privacy-guide/

Couldn't agree more. The way agentic browsers redefine security rendering traditional policies like SOP and CORS obsolete is genuinely concerning. What kind of innovative security models do you envision emerging to tackle these new instruction injection vulnerabilities? Your analysis here is really insightful.